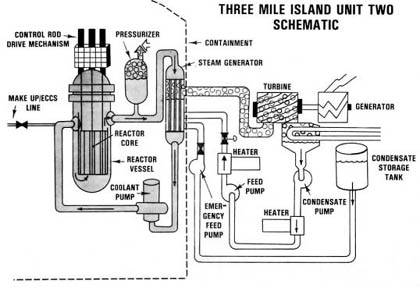

The accident began at 4:00 a.m. on March 28, 1979. For an unknown reason, the feed pump (in the turbine water loop; see the schematic below) stopped operating. Without this pump, the turbine water could not remove heat from the steam generator. When this happened, the control rods automatically dropped into the reactor, stopping the fission process. However, the radioactive fission products still produced heat so the temperature and pressure started to rise. To reduce the pressure, the valve on the pressurizer, called the pilot-operated relief valve (PORV), opened. Up to this time, everything operated as designed.

Drawing from Metropolitan Edison Co. “Report to the Met-Ed Community” May 30, 1979

When the pressure in the pressurizer dropped to a prescribed value, the PORV was suppose to close; it did not. The accident was now underway. The control panel had an indicator that showed the valve to be closed, (i.e., power was going to the valve to close it) but there was no way to determine that the valve was actually closed. With the valve open, steam and water escaped the pressurizer; this water flowed into a drain tank (not shown in the schematic).

When the feed pump failed, the emergency feed pump should have turned on to keep the turbine water flowing. That pump was tested 42 hours prior and was functional. However, to perform the test, workers must close a valve, perform the test, then open that valve. Apparently the workers forgot to open the valve so the emergency water did not flow. Now the reactor was losing water and getting hotter. With the loss of water (and no air or steam in the pressurizer) the pressure dropped.

When the pressure dropped, some of the water in the reactor turned to steam. This had two major consequences; first it forced water into the pressurizer and filled it completely, and second, steam rather than water surrounded some of the reactor fuel. Steam does not conduct heat as well as water, so the fuel pellets heated up.

In case of an accident, a nuclear power plant has tanks of water with pumps that can quickly introduce water to cool the reactor. One of these automatically started. The operators noticed this, but when they looked at the indicators for the pressurizer, these indicators showed that the pressurizer was full of water (which it was because of the steam in the reactor core area). A full pressurizer meant that the operators could not control the pressure, so they turned off the entering water.

Now the situation went from bad to worse. About 100 minutes after the accident started, steam bubbles appeared in the coolant pumps, causing them to vibrate. Fearing a compete failure of these pumps, the operators turned them off. With no water flowing into the reactor and water and steam escaping the reactor, large portions of the reactor core became uncovered. With no water to remove the heat, the fuel pellets started to melt, resulting in a partial meltdown.

Finally, one operator surveyed the data and concluded that the PORV was open, so at 6:18 a.m., they closed the valve and then introduced water into the reactor, ending the immediate emergency. However, between the time that the operators shut off the pumps and when the valve was closed, the core was uncovered enough to cause some fuel to melt. At the time of the accident, nobody thought that a major portion of the fuel had melted. When the reactor was opened months later, they were surprised to find that about 60% of the core had actually melted.

While the reactor core was melting, the hot zirconium (that held the fuel) was reacting with the water. This chemical reaction produced hydrogen gas, which is combustible. Some of the hydrogen gas escaped from the reactor and into the containment building. The operators were unaware of the presence of hydrogen until something ignited it around 2:00 p.m. The burn lasted for six to eight seconds, but did no damage to any systems in the building. However, the reactor vessel still contained hydrogen, but nobody seemed to address this problem in light of other, more serious, problems. When somebody gave it some thought two days later, the great fear was that the hydrogen might explode, causing a breach of the reactor vessel and maybe of the containment building. Once the presence of hydrogen was verified, the hydrogen was sent though neutralizers and by the fourth day most of the hydrogen was gone. Actually the fear of an explosion was unfounded. To burn, hydrogen must combine with oxygen, but no oxygen was present in the reactor vessel. However, the fear of an explosion caused many of the public to evacuate the area around TMI.

During these first few hours of the accident, all the action occurred in the reactor building. However, the water that escaped through the pressurizer valve had filled the drain tank and overflowed onto the floor in the Auxiliary Building. Because the core had been uncovered resulting in some core melt, radioactivity had escaped to the reactor water and some of that water was now in the Auxiliary Building. Some of the radioactivity was xenon and krypton (noble gases) and iodine. The gasses could not be contained, so they soon leaked into the atmosphere, exposing the public to radiation. Although the release stacks on the Auxiliary building contained radiation monitors, they were designed for much smaller releases. Therefore the actual radioactivity that was released was never measured, but from later calculations, the scientific community estimated that about 17 million Curies* escaped from the reactor to the Auxiliary building. The Auxiliary building served as something like a holding tank, which allowed some of the radioactivity to decay before entering the atmosphere. As a result, a little more than half, 9 million Curies, made it into the environment.

As a result of these noble gas releases, the public received some radiation dose. The actual dose received by any one person will never be known, but experts, according to testimony in the TMI Litigation, gave limits in the 25 to 50 mrem range (TMI Litigation Consolidated Proceedings, Civil Action No. 1:CV-88-1452; Judge Sylvia Rambo). Normal background radiation, excluding radon (cosmic rays, radioactivity in the body, and terrestrial radiation), is about 100 mrem per year in the central Pennsylvania area. (For further discussion on radiation dose and health effects, see Chapters 2 and 3 in The 3R’s; Radiation, Risk, and Reason) In addition, researchers did not find any radioactive iodine from the accident in food and milk samples. The final result of the investigations into the doses indicated that population dose did give the public an increased risk of cancer, but at most, one person may get a fatal cancer.

For a more in-depth description of the accident, see the Rogovin Report. This is summarized at: Rogovin Report Summary.

For an in-depth study of the health effects, see the studies done by the University of Pittsburgh (the second is an abstract only):

Study 1

For explanations for many health effects of plants and animals, see:

Investigations of Reported Plant and Animal Health Effects in the Three Mile Island Area; NUREG-0738

For more information on the Sylvia Rambo decision, see the PBS Frontline Site.

*Activity is the rate at which the radioactive material changes, or decays. The official unit is one decay per second which is called a Becquerel (Bq). The older, more traditional unit, is the Curie, which is 37 billion decays per second.